Is Red Pandas Part of the Panda Family

| Red panda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| | |

| CITES Appendix I (CITES)[ane] | |

| Scientific nomenclature | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Guild: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ailuridae |

| Genus: | Ailurus F. Cuvier, 1825 |

| Species: | A. fulgens |

| Binomial name | |

| Ailurus fulgens F. Cuvier, 1825 | |

| Subspecies | |

| A. f. fulgens F. Cuvier, 1825 | |

| |

| Range of the red panda | |

The scarlet panda (Ailurus fulgens), besides known equally the lesser panda, is a small mammal native to the eastern Himalayas and southwestern Prc. It has dense reddish-brown fur, white-lined ears, a mostly white muzzle and a ringed tail. Its head-to-body length is 51–63.5 cm (xx.1–25.0 in) with a 28–48.five cm (11.0–19.i in) tail, and it weighs betwixt 3.2 and fifteen kg (7.1 and 33.1 lb). Information technology is well adjusted to climbing due to its flexible joints and curved semi-retractile claws.

The red panda was first described in 1825. The ii currently recognised subspecies, the Himalayan and the Chinese red panda, genetically diverged most 250,000 years ago. The ruby panda'south identify on the evolutionary tree has been debated, but modern genetic testify places it in shut analogousness with raccoons and weasels. It is not closely related with the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), which is a carry, though both possess elongated wrist basic or "imitation thumbs" used for grasping bamboo. The evolutionary lineage of the ruby panda stretches back around 25 to xviii million years ago, equally indicated past extinct fossil relatives found in Eurasia and Due north America.

The scarlet panda inhabits coniferous forests too equally temperate broadleaf and mixed forests, favouring steep slopes with dense bamboo cover shut to water sources. It is alone and largely arboreal. It feeds mainly on bamboo shoots and leaves, simply likewise on fruits and blossoms. Red pandas mate in early spring, with the females giving birth to litters of upwardly to 4 cubs in summer. Information technology is threatened by poaching also equally destruction and fragmentation of habitat due to deforestation. The species has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2015. Information technology is protected in all range countries.

Community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in Nepal, Bhutan and northeastern Republic of india; in People's republic of china, it benefits from nature conservation projects. The International Red Panda Day is celebrated annually in September. Regional captive breeding programmes for the red panda have been established in zoos around the world. It is featured in animated movies, video games, comic books and equally the namesake of companies and music bands.

Etymology

The name "panda" is thought to have originated from the red panda's local Nepali name पञ्जा pajā "claw" or पौँजा paũjā "paw".[iii] [4] In English, it was simply called "panda"; when the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) was formally described and named in 1869, it became known as the "reddish panda" or "lesser panda" to distinguish information technology from the larger animal.[iv] The genus name Ailurus is adopted from the ancient Greek word αἴλουρος ( ailouros ), significant "cat".[5] The specific epithet fulgens is Latin for "shining, vivid".[6] [4]

Taxonomy

The red panda was classified and formally described in 1825 by Frederic Cuvier, who gave it its electric current scientific name Ailurus fulgens. Cuvier's description was based on zoological specimens, including skin, paws, jawbones and teeth "from the mountains north of Republic of india", also as an account by Alfred Duvaucel.[7] [8] The crimson panda was described earlier by Thomas Hardwicke in 1821, but his paper was published only vi years later.[4]

In 1847, Brian Houghton Hodgson described a red panda from the Himalayas, for which he proposed the name Ailurus ochraceus.[9] For a long time, Hodgson's account was the only information available about the crimson panda'due south behaviour in the wild.[4] In 1902, Oldfield Thomas described a skull of a male blood-red panda specimen nerveless in Sichuan by Frederick William Styan under the name Ailurus fulgens styani.[ii]

Subspecies and species

The modern carmine panda is the only recognised species of the genus Ailurus. It is traditionally divided into two subspecies: the Himalayan red panda (A. f. fulgens) and the Chinese carmine panda (A. f. styani). The Himalayan subspecies has a straighter profile, a lighter coloured forehead and ochre-tipped hairs on the lower back and rump. The Chinese subspecies has a more curved forehead, steeper muzzle gradient, a darker coat with a redder, less white face and more contrast betwixt the tail rings.[10]

In 2020, results of a genetic assay of carmine panda samples showed that the red panda populations in the Himalayas and China were separated nigh 250,000 years ago. The researchers suggested that the two subspecies should be treated as distinct species. Red pandas in southeastern Tibet and northern Myanmar were found to be office of styani, while those of southern Tibet were of fulgens (sensu stricto).[11] DNA sequencing of 132 red panda faecal samples collected in Northeast India and China as well showed two distinct clusters indicating that the Siang River in Arunachal Pradesh constitutes the purlieus between the Himalayan and Chinese ruby pandas.[12] They probably diverged due to glaciation events on the southern Tibetan Plateau in the Pleistocene.[13]

Phylogeny

The placement of the cerise panda on the evolutionary tree has been debated. In the first half of the 20th century, various scientists placed it in the family Procyonidae with raccoons and their allies. At the fourth dimension, most prominent biologists likewise considered the cherry panda to exist related to the behemothic panda and classified both in the subfamily Ailurinae within Procyonidae. The behemothic panda would somewhen be found to be a comport. A 1982 study examined the similarities and differences in the skull between the red panda and the behemothic panda, other bears and procyonids, and placed the species in its ain family Ailuridae. The author of the study considered the cerise panda to be more closely related to bears.[ten]

A 1995 mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis revealed that the red panda has close affinities with procyonids.[14] Further genetic studies have placed the red panda within the clade Musteloidea, which too includes Procyonidae, Mustelidae (weasels and relatives) and Mephitidae (skunks and relatives). The following cladogram is based on the molecular phylogeny of six genes,[15] with the musteloids updated following a multigene analysis.[xvi]

Fossil tape

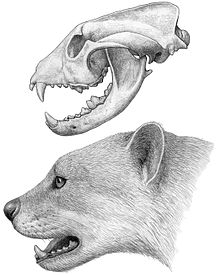

Reconstructed skull and caput of Simocyon

The family unit Ailuridae appears to have originated in Europe erstwhile during the Tardily Oligocene or Early Miocene, about 25 to 18 million years ago. The primeval member Amphictis is known from its ten cm (4 in) skull and may have been effectually the same size as the modern species. Its dentition consists of pointed premolars, relatively sharp-edged carnassials (P4 and m1) and molars with grinding surfaces (M1, M2 and m2), suggesting that it had a generalized carnivorous diet. Its placement within Ailuridae is based on the lateral grooves on its canine teeth. Other early or basal aliruds include Alopecocyon and Simocyon, whose fossils accept been institute throughout Eurasia and North America dating from the Middle Miocene, the latter of which survived into the Early on Pliocene. Both have like teeth to Amphictis and thus had a like diet.[17] The puma-sized Simocyon was likely a tree-climber and shares a "false thumb"—an extended wrist bone—with the modern species, suggesting the bagginess was an adaptation to arboreal locomotion and not to feed on bamboo.[17] [18]

Later and more avant-garde ailruds are classified in the subfamily Ailurinae and are known as the "true" red pandas. These animals were smaller and more adjusted for an omnivorous or herbivorous nutrition. The earliest known true panda is the species Magerictis imperialensis from the Middle Miocene of Spain and known only from a single tooth, a lower 2nd molar. The tooth shows both ancestral and new characteristics having a relatively low and uncomplex crown simply also an elongated crushing surface and well-differentiated molar cusps like later species.[19] Later ailurines include Pristinailurus bristoli of Late Miocene-Early on Pliocene eastern North America[19] [xx] and species of the genus Parailurus which first appear in Early Pliocene Europe, spreading beyond Eurasia into Due north America.[19] [21] These animals are likely to exist part of a sis taxon to the lineage of the mod panda. In contrast to the herbivorous modern species, these ancient pandas were likely omnivores, possessing many cusps on the molars simply retaining precipitous premolars.[xix] [22] [20]

The primeval fossil record of the modern genus Ailurus date no before than the Pleistocene and appears to have been limited to Asia. The modern panda's lineage became adapted for a specialized bamboo nutrition, having tooth-like premolars and more highly crowned cusps.[19] The simulated thumb would secondarily gain a role in feeding.[17] [xviii]

Genomics

Analysis of 53 red panda samples from Sichuan and Yunnan showed a high level of genetic diversity.[23] The total genome of the ruddy panda was sequenced in 2017. Researchers accept compared information technology to the genome of the giant panda to learn the genetics of convergent development, as both species have faux thumbs and are adjusted for a specialized bamboo diet despite having the digestive system of a carnivore. Both pandas show modifications to certain limb development genes (DYNC2H1 and PCNT), which may play roles in the development of the thumbs.[24] In switching from a carnivorous to a herbivorous diet, both species have reactivated taste receptor genes used for detecting bitterness, though the specific genes are different.[25]

Characteristics

Ruby panda skull

Red panda face up

The reddish panda'southward coat is mainly red or orange-brownish with a black belly and legs. The face is more often than not white and has red marks that stretch from the side bending of the eyes to the corners of the mouth. The inside of the ears are covered in white fur with a red patch in the centre.[26] Its bushy tail has alternating rings of red and buff.[27] [26] The colouration appears to serve as camouflage in a habitat with scarlet moss- and white lichen-covered trees. The fur consists of coarse baby-sit hairs with a soft dense, woolly undercoat.[27] The guard hairs on the back accept a circular cross-section and are 47–56 mm (one.ix–2.2 in) long. It has moderately long whiskers effectually the mouth, lower jaw and chin.[26]

The ruby-red panda has a head-torso length of 51–63.5 cm (twenty.1–25.0 in) with a 28–48.5 cm (11.0–xix.i in) tail. The Himalayan red panda is recorded to weigh 3.two–ix.4 kg (7.1–xx.7 lb), while the Chinese red panda weighs 4–xv kg (eight.8–33.1 lb) for females and four.two–13.4 kg (9.3–29.5 lb) for males.[26] The panda has a relatively small head with a reduced snout and triangular ears, though proportionally larger than in similarly sized raccoons, while the limbs are nearly equal in length.[26] [27] The cerise panda has five curved digits on each foot, which cease in curved semi-retractile claws that assistance in climbing.[27] The pelvis and hindlimbs have flexible joints, adaptations for an arboreal quadrupedal lifestyle.[28] While not prehensile, the tail acts as support and weigh when climbing.[27]

The forepaws possess a "false thumb", which is an extension of a wrist bone, the radial sesamoid establish in many carnivorans. This pollex allows the animal to hold onto bamboo stalks and separate leaves, and both the digits and wrist bones give the red panda remarkable dexterity. The ruby-red panda shares this feature with the giant panda, which has a larger sesamoid that is more compressed at the sides. In addition, the red panda's sesamoid has a more concave tip while the behemothic panda's hooks in the middle.[29]

Its skull is broad, and its lower jaw is robust.[27] [26] Yet, because information technology eats the less fibrous parts of bamboo, the leaves and stems, it has less-developed chewing muscles than the behemothic panda. The digestive tract of the cerise panda is also typical of a carnivore, beingness fairly short, at only 4.2 times its trunk length, with a simple stomach, no articulate distinction between the ileum and the colon, and no caecum.[26] Microbes in its gut may play a office in its processing of bamboo; the microbiota community in the red panda is less diverse than in other mammals.[30]

Distribution and habitat

The red panda is distributed from western Nepal, the states of Sikkim, West Bengal and Arunachal Pradesh in India, Bhutan and southern Tibet to northern Myanmar and China's Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.[1] The global potential habitat of the ruby panda has been estimated to comprise 47,100 km2 (18,200 sq mi) at almost; this habitat is located in the temperate climate zone of the Himalayas with a mean annual temperature range of eighteen–24 °C (64–75 °F).[31] Throughout this range, it has been recorded at elevations of ii,000–4,300 thou (6,600–xiv,100 ft).[32] [33] [34] [35] [36]

| Country | Estimated size[31] |

|---|---|

| Nepal | 22,400 km2 (8,600 sq mi) |

| China | 13,100 km2 (five,100 sq mi) |

| Bharat | v,700 kmtwo (2,200 sq mi) |

| Myanmar | v,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) |

| Kingdom of bhutan | 900 km2 (350 sq mi) |

| Full | 47,100 km2 (18,200 sq mi) |

In Nepal, it lives in half-dozen protected surface area complexes within the Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests ecoregion.[34] The westernmost records to date were obtained in iii customs forests in Kalikot District in 2019.[37] Panchthar and Ilam Districts represent its easternmost range in the country, where its habitat in forest patches is surrounded by villages, livestock pastures and roads.[38] The metapopulation in protected areas and wild fauna corridors in the Kangchenjunga landscape of Sikkim and northern Due west Bengal is partly continued through erstwhile-growth forests outside protected areas.[39] Forests in this landscape are dominated by Himalayan oaks (Quercus lamellosa and Q. semecarpifolia), Himalayan birch (Betula utilis), Himalayan fir (Abies densa), Himalayan maple (Acer caesium) with bamboo, Rhododendron and some black juniper (Juniperus indica) shrub growing in the understoreys.[32] [forty] [41] [42] Records in Kingdom of bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh's Pangchen Valley, W Kameng and Shi Yomi districts indicate that information technology frequents habitats with Yushania and Thamnocalamus bamboo, medium-sized Rhododendron, Sorbus and Castanopsis trees.[33] [43] [44] In People's republic of china, information technology inhabits the Hengduan Mountains subalpine conifer forests and Qionglai-Minshan conifer forests in the Hengduan, Qionglai, Xiaoxiang, Daxiangling and Liangshan Mountains in Sichuan.[45] In the adjacent Yunnan province, it was recorded merely in the northwestern montane office.[46] [47]

The blood-red panda prefers microhabitats within 70–240 yard (230–790 ft) of water sources.[48] [49] [50] [51] Fallen logs and tree stumps are of import habitat features, every bit they facilitate access to bamboo leaves.[52] Red pandas have been recorded to utilise steep slopes of more than twenty° and stumps exceeding a bore of 30 cm (12 in).[48] [53] Red pandas observed in Phrumsengla National Park used foremost easterly and southerly slopes with a mean slope of 34° and a awning cover of 66 percent that were overgrown with bamboo nearly 23 m (75 ft) in height.[49] In Dafengding Nature Reserve, it prefers steep southward-facing slopes in winter and inhabits forests with bamboo 1.5–2.5 m (4 ft 11 in – 8 ft 2 in) tall.[54] In Gaoligongshan National Nature Reserve, information technology inhabits mixed coniferous forest with a dense awning embrace of more than 75 percent, steep slopes and a density of at least 70 bamboo plants/chiliad2 (six.5 bamboo plants/sq ft).[55] In China's Fengtongzhai and Yele Natural Reserves, the red panda selects steep slopes and a high density of bamboo stems, fallen logs and stumps, whereas the behemothic panda prefers gentle slopes with taller bamboo simply lower densities of stems, logs and stumps. Such niche separation lessens competition between the ii bamboo-eating species.[48] [52]

Behaviour and environmental

Red panda sleeping on a tree

The red panda is hard to observe in the wild,[56] and most studies on its behaviour have taken place in captivity.[57] The red panda appears to be both nocturnal and crepuscular, sleeping in betwixt periods of activeness at night. It typically rests or sleeps in trees or other elevated spaces, stretched out on a branch with legs dangling when it is hot, and curled upwards with its tail over the face when it is cold. It is adapted for climbing and descends to the ground head-get-go with the hindfeet belongings on to the middle of the tree trunk. It moves quickly on the basis by trotting or bounding. Its lifespan in captivity reaches fourteen years.[27]

Adult pandas are by and large lonely and territorial. Individuals marker their home range or territorial boundaries with urine, faeces and secretions from the anal and surrounding glands. Odor-marking occurs more on the ground, and males marking more than oftentimes and for longer periods than females.[27] In Red china'due south Wolong National Nature Reserve, the habitation range of a radio-collared female was 0.94 km2 (0.36 sq mi), while that of a male was i.11 kmtwo (0.43 sq mi).[58] A ane-year-long monitoring study of ten red pandas in eastern Nepal showed that the iv males had median dwelling house ranges of 1.73 kmii (0.67 sq mi) and the six females of 0.94 km2 (0.36 sq mi) inside a forest cover of at least xix.2 ha (47 acres). The females travelled 419–841 m (1,375–two,759 ft) per day and the males 660–1,473 m (ii,165–four,833 ft). In the mating season from January to March, adults travelled a mean of 795 m (two,608 ft) and subadults a mean of 861 grand (two,825 ft).[38] They all had larger dwelling house ranges in areas with depression forest cover and reduced their activity in areas that were disturbed by people, livestock and dogs.[59]

Nutrition and feeding

The ruddy panda is largely herbivorous and feeds primarily on bamboo, mainly the genera Phyllostachys, Sinarundinaria, Thamnocalamus and Chimonobambusa.[60] It likewise feeds on fruits, blossoms, acorns, eggs, birds and pocket-sized mammals. It mainly eats the leaves of bamboo, which are ofttimes the only bachelor nutrient item in the wintertime and the most mutual food for the rest of the yr.[61] In Wolong National Nature Reserve, leaves of Bashania fangiana were found in almost 94 percent of analysed droppings, and its shoots were found in 59 per centum of the debris establish in June.[58]

The diet of red pandas monitored at three sites in Singalila National Park for two years consisted of 40–83 percent Yushania maling and 51–91.2 percent Thamnocalamus spathiflorus bamboos[a] supplemented by bamboo shoots, Actinidia strigosa fruits and seasonal berries.[64] In this national park, red panda droppings too contained remains of silky rose and bramble fruit species in the summertime flavor, Actinidia callosa in the post-monsoon season, and Merrilliopanax alpinus, whitebeam (Sorbus cuspidata) and tree rhododendron in both seasons. Droppings were plant on 23 constitute species including the rock oak (Lithocarpus pachyphyllus), Campbell's magnolia (Magnolia campbellii), chinquapin (Castanopsis tribuloides), Himalayan birch, Litsea sericea and the holly species Ilex fragilis.[65] In Nepal's Rara National Park, Thamnocalamus was plant in 100 per centum of droppings sampled, both before and after the monsoon.[66] Its summer nutrition in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve besides includes some lichens and barberries.[40] In Bhutan'south Jigme Dorji National Park, red panda faeces constitute in the fruiting flavour contained seeds of Himalayan ivy (Hedera nepalensis).[51]

The cerise panda grabs food with one of its front paws and normally eats sitting down or continuing, but sometimes lays on its back. When foraging for bamboo, it grabs the establish by the stem and bends it down so the leaves are within attain of the jaws. Information technology inserts them into the side and shears and chews them. Information technology nips small food similar blossoms, berries and small leaves with the incisors.[27] Having the digestive system of a carnivore, the ruby panda is a poor processor of bamboo, which passes through its gut in two to four hours. It hence selects the more nutritious establish matter, such equally tender leaves and shoots, and consumes them in big quantities. It eats over i.5 kg (3 lb 5 oz) of fresh leaves or 4 kg (nine lb) of fresh shoots in a day and tin can digest crude proteins and fats more easily than fibres and lignin in the bamboo leaves. Bamboo is virtually digestible in summertime and fall but to the lowest degree in winter, and shoots are more digestible than leaves.[67]

Advice

Sounds of red panda twittering

At least vii different vocalisations take been recorded in the red panda, comprising growls, barks, squeals, hoots, bleats, grunts and twitters. Growling, barking, grunting and squealing are produced during fights and aggressive chasing. Hooting is made in response to being approached by another individual. Bleating is recorded after scent-marking and sniffing. Males may squeal during courting, especially before mounting. Twittering is made by mating females.[68] During both play fighting and aggressive fighting, individuals curvation their backs and tails while slowly moving their heads up and downward. They then plow their heads while jaw-clapping, motility their heads side to side and raise a forepaw with an intent to strike. They stand on their hind legs and raise the forelimbs above the head earlier lunging. 2 individuals "stare" each other from a distance.[27]

Reproduction and parenting

Red panda disposed its cub

Carmine pandas are "long-day" breeders, meaning that convenance occurs as the length of daylight increases following the winter solstice. Mating thus occurs generally between Jan and March, with births taking identify from May to August. For captive pandas in the southern hemisphere, reproduction is delayed past vi months. Oestrous lasts a day, and females can enter oestrous multiple times a season, but the length of intervals betwixt each bicycle is non clear.[69]

As the breeding flavor begins, in that location are increased interactions between males and females, who will rest, move and feed close to each other. Oestrous females are observed to mark more often and more vigorously and males will sniff their anogenital region. Receptive females brand tail-flicks and position themselves in a lordosis pose, with the front lowered and the back arched. Copulation involves the male mounting the female person from behind and on top, though contiguous matings besides as belly-to-back matings while lying on the sides accept been observed. The male usually does not bite the female's neck merely volition take hold of her sides with his forepart paws. Mountings are ii–25 minutes long, and the couple grooms each other betwixt mounting bouts.[69]

Gestation lasts nigh 158 days. Prior to giving birth, the female person selects a denning site, such as a tree, log or stump hollow or rock cleft, and builds a nest using material from nearby, such as twigs, sticks, branches, bark bits, leaves, grass and moss.[56] Litters typically consist of 1 to four cubs that are built-in fully furred but blind. They are entirely dependent on their mother for the first 3 to four months until they emerge from the nest. They nurse for their first five months.[70] Mother and offspring stay together until the next breeding. Cubs reach their adult size at around 12 months and sexual maturity at around 18 months.[27] Ii radio-collared cubs in eastern Nepal separated from their mothers at the historic period of seven–eight months and left their birth areas three weeks later. They reached new home ranges inside 26–42 days and became residents after exploring them for 42–44 days.[38]

Diseases

Faecal samples of red panda collected in Nepal contained parasitic protozoa, amoebozoans, roundworms, trematodes and tapeworms.[71] [72] Roundworms, tapeworms and coccidia were besides found in cherry-red panda scat nerveless in Rara and Langtang National Parks.[73] Fourteen red pandas at the Knoxville Zoo suffered from severe ringworm, so the tails of two were amputated.[74] Chagas disease was reported as the crusade of death of a blood-red panda kept in a Kansas zoo.[75] Amdoparvovirus was detected in the scat of six blood-red pandas in the Sacramento Zoo.[76] Eight captive red pandas in a Chinese zoo suffered from shortness of jiff and fever presently earlier they died of pneumonia; autopsy revealed that they had antibodies to the protozoans Toxoplasma gondii and Sarcocystis species indicating that they were intermediate hosts.[77] A captive red panda in the Chengdu Research Base of Behemothic Panda Breeding died of unknown reasons; an autopsy showed that its kidneys, liver and lungs were damaged past a bacterial infection caused past Escherichia coli.[78]

Threats

The primary threats to the red panda are destruction and fragmentation of habitat caused by multiple circumstances such every bit increasing human being population, deforestation, illegal collection of not-timber forest products and poaching, disturbances by herders and livestock and lack of police enforcement.[1] Small-scale groups of animals with little opportunity for exchange betwixt them face the run a risk of inbreeding, decreased genetic diversity, and even extinction. In addition, clearcutting for firewood or agronomics and hillside terracing removes onetime trees that provide maternal dens and decreases the ability of some bamboo species to regenerate.[79] The cut lumber stock in Sichuan alone reached 2,661,000 m3 (94,000,000 cu ft) in 1958–1960, and 3,597.9 km2 (one,389.2 sq mi) of red panda habitat were logged between the mid 1970s and tardily 1990s.[46]

Deforestation inhibits the dispersal of ruddy pandas and leads to severe fragmentation of the population; trampling by livestock depresses bamboo growth.[80] Throughout Nepal, the reddish panda habitat outside protected areas is negatively affected by solid waste, livestock trails and herding stations, and people collecting firewood and medicinal plants.[40] [81] Threats identified in Nepal's Lamjung District include grazing by livestock during seasonal transhumance, man-made wood fires and the collection of bamboo as cattle fodder in winter.[82] Vehicular traffic is a pregnant barrier to ruddy panda motion between habitat patches.[59]

In Nepal'due south Taplejung District, red panda claws are used for treating epilepsy; its skin is used in rituals for treating ill people, making hats, scarecrows and decorating houses. Between 2008 and 2018, 121 skins were confiscated in the country.[83] In Myanmar, the red panda is threatened past hunting using guns and traps; since roads to the border with China were built starting in the early 2000s, red panda skins and live animals are traded and smuggled beyond the border.[36] In southwestern Red china, the cerise panda is hunted for its fur, especially for the highly valued bushy tails, from which hats are produced. The fur is used for local cultural ceremonies. At weddings, the bridegroom traditionally carries the hide. The "skilful-luck amuse" red panda-tail hats are too used by local newlyweds. A 40 percent subtract in cerise panda populations has been reported in China over the last 50 years, and populations in western Himalayan areas are considered to exist smaller.[46] Between 2005 and 2017, 35 live and seven dead crimson pandas were confiscated in Sichuan, and several traders were sentenced to 3–12 years of imprisonment. A month-long survey of 65 shops in nine Chinese counties in the spring of 2017 revealed only 1 in Yunnan offered hats made of red panda skins, and carmine panda tails were offered in an online forum.[84]

Conservation

The ruby panda is listed in CITES Appendix I and protected in all range countries; hunting is illegal. Information technology has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Crimson List since 2008 considering the global population is estimated at 10,000 individuals, with a decreasing population trend. A large extent of its habitat is part of protected areas.[1]

| State | Protected areas |

|---|---|

| Nepal | Api Nampa Conservation Area, Khaptad National Park, Rara National Park, Annapurna Conservation Area, Manaslu Conservation Area, Langtang National Park, Gaurishankar Conservation Surface area, Sagarmatha National Park, Makalu Barun National Park, Kanchenjunga Conservation Area[34] |

| India | Khangchendzonga National Park, Singalila National Park, Varsey Rhododendron Sanctuary, Shingba Rhododendron Sanctuary, Fambong Lho Wild animals Sanctuary, Kyongnosla Alpine Sanctuary, Pangolakha Wild animals Sanctuary, Maenam Wildlife Sanctuary,[39] Namdapha National Park[85] |

| Bhutan | Jigme Khesar Strict Nature Reserve, Jigme Dorji National Park, Wangchuck Centennial National Park, Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bumdeling Wild fauna Sanctuary, Sakteng Wild fauna Sanctuary, Phrumsengla National Park, Jomotsangkha Wild animals Sanctuary[33] |

| Myanmar | Hkakaborazi National Park, Hponkanrazi Wildlife Sanctuary,[86] Imawbum National Park[36] |

| China | Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon Nature Reserve[87] and half dozen more than nature reserves in Tibet, 8 in Yunnan and 32 in Sichuan[88] |

Closeup look of red panda

A cherry-red panda anti-poaching unit and community-based monitoring have been established in Langtang National Park. Members of Community Forest User Groups also protect and monitor ruby panda habitats in other parts of Nepal.[89] Community outreach programs have been initiated in eastern Nepal using data boards, radio broadcasting and the annual International Red Panda Day in September; several schools endorsed a blood-red panda conservation manual equally role of their curricula.[90]

Since 2010, community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in x districts in Nepal that aim to help villagers reduce their dependence on natural resources through improved herding and food processing practices and alternative income possibilities. The Nepal government ratified a five-year Red Panda Conservation Activeness Plan in 2019.[91] From 2016 to 2019, 35 ha (86 acres) of high-elevation rangeland in Merak, Bhutan, was restored and fenced in cooperation with 120 herder families to protect the red panda wood habitat and improve communal pasture.[92] Villagers in Arunachal Pradesh established two community conservation areas to protect the cherry panda habitat from disturbance and exploitation of forest resources.[43] China has initiated several projects to protect its environment and wildlife, including Grain for Green, The Natural Forest Protection Project and the National Wild fauna/Natural Reserve Construction Project. For the final projection, the cerise panda is not listed as a key brute for protection only may do good from the protection of the giant panda and golden snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana), with which it overlaps in range.[88]

In captivity

The London Zoo acquired two red pandas in 1869 and 1876 that were defenseless in Darjeeling. The Calcutta Zoo received a live red panda in 1877, the Philadelphia Zoo in 1906, and Artis and Cologne Zoos in 1908. In 1908, the first cherry panda cubs were born in an Indian zoo. In 1940, the San Diego Zoo imported 4 red pandas via India that had been defenseless in Nepal; their first litter was born in 1941. Cubs that were born later were sent to other zoos so that about 250 red pandas had been exhibited in zoos by 1969.[93] The Taronga Conservation Society started keeping red pandas in 1977.[94]

In 1978, the International Red Panda Studbook was prepare upwards, followed past the Red Panda European Endangered Species Programme in 1985. Members of international zoos ratified a global primary plan for the captive breeding of the reddish panda in 1993. Past the end of 2019, 182 European zoos kept 407 red pandas.[95] Past late 2015, 219 red pandas lived in 42 zoos in Japan.[96] The Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park participates in the Red Panda Species Survival Program and kept about 25 crimson pandas past 2016.[97] Regional captive breeding programmes have besides been established in N American, Australasian and South African zoos.[iv]

Cultural significance

The red panda is depicted in a hunting scene of a Chinese Chou Dynasty scroll dating to the 13th century. In western Nepal, shamans of an indigenous group use their skin and fur in their ritual dresses and believe that information technology protects against evil spirits. Tribal people in Arunachal Pradesh and Yi people also believe that it brings skillful luck to wear scarlet panda tails or hats made of its fur. People in central Kingdom of bhutan consider red pandas to exist reincarnations of Buddhist monks.[98]

A watercolour painting by an Indian artist dating to 1820 is amongst the earliest known paintings of the red panda.[99] The red panda was recognized every bit the state fauna of Sikkim in the early 1990s and was the mascot of the Darjeeling Tea Festival.[79] Anthropomorphic cherry-red pandas feature in animated movies and Television receiver series such equally Bamboo Bears, Barbie as the Isle Princess, the Kung Fu Panda franchise, Aggretsuko and Turning Cherry, and in several video games and comic books. The red panda is the namesake of the Firefox browser, and it has been used equally the namesake of companies and music bands.[98]

Notes

- ^ Labelled Arundinaria maling and A. aristata respectively, which are junior synonyms of the species listed here.[62] [63]

References

- ^ a b c d east Glatston, A.; Wei, F.; Than Zaw & Sherpa, A. (2017) [errata version of 2015 assessment]. "Ailurus fulgens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: eastward.T714A110023718. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b Thomas, O. (1902). "On the Panda of Sze-chuen". Register and Magazine of Natural History. 7. X (57): 251–252. doi:10.1080/00222930208678667.

- ^ Turner, R. L. (1931). "पञ्जा". A Comparative and Etymological Lexicon of the Nepali Linguistic communication. London: 1000. Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 359.

- ^ a b c d e f Glatston, A. R. (2021). "Introduction". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. xix–xxix. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "αἴλουρος". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Printing.

- ^ Lewis, C. T. A. & Short, C. (1879). "fulgens". Latin Dictionary (Revised, enlarged, and in corking part rewritten ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Cuvier, F. (1825). "Panda". In Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Due east.; Cuvier, F. (eds.). Histoire naturelle des mammifères, avec des figures originales, coloriées, dessinées d'après des animaux vivans: publié sous l'autorité de l'administration du Muséum d'Histoire naturelle. Vol. Tome v. Paris: A. Belin. p. LII i–3.

- ^ Cuvier, One thousand. (1829). "Le Panda éclatant". Le règne animal distribué d'après son arrangement. Vol. Tome 1. Chez Déterville, Paris. p. 138.

- ^ Hodgson, B. H. (1847). "On the Cat-toed subplantigrades". Periodical of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. sixteen (two): 1113–1128.

- ^ a b Groves, C. (2021). "The taxonomy and phylogeny of Ailurus". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biological science and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Bookish Press. pp. 95–117. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ Hu, Y.; Thapa, A.; Fan, H.; Ma, T.; Wu, Q.; Ma, Southward.; Zhang, D.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Yan, Fifty. & Wei, F. (2020). "Genomic evidence for two phylogenetic species and long-term population bottlenecks in red pandas". Science Advances. 6 (9): eaax5751. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5751H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5751. PMC7043915. PMID 32133395.

- ^ Joshi, B. D.; Dalui, S.; Singh, S. 1000.; Mukherjee, T.; Chandra, M.; Sharma, Fifty. K. & Thakur, M. (2021). "Siang river in Arunachal Pradesh splits Carmine Panda into two phylogenetic species". Mammalian Biology. 101 (1): 121–124. doi:10.1007/s42991-020-00094-y. S2CID 231811193.

- ^ Dalui, S.; Singh, S. K.; Joshi, B. D.; Ghosh, A.; Basu, Southward.; Khatri, H.; Sharma, L. K.; Chandra, K. & Thakur, M. (2021). "Geological and Pleistocene glaciations explain the demography and disjunct distribution of Cherry Panda (A. fulgens) in eastern Himalayas". Scientific Reports. xi (1): 65. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80586-6. PMC7794540. PMID 33420314.

- ^ Pecon-Slattery, J. & O'Brien, S. J. (1995). "Molecular phylogeny of the crimson panda (Ailurus fulgens)". The Journal of Heredity. 86 (half dozen): 413–422. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111615. PMID 8568209.

- ^ Flynn, J. J.; Finarelli, J. A.; Zehr, S.; Hsu, J. & Nedbal, Yard. A. (2005). "Molecular phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Assessing the touch of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships". Systematic Biology. 54 (2): 317–337. doi:10.1080/10635150590923326. PMID 16012099.

- ^ Law, C. J.; Slater, 1000. J. & Mehta, R. S. (2018). "Lineage Diverseness and Size Disparity in Musteloidea: Testing Patterns of Adaptive Radiations Using Molecular and Fossil-Based Methods". Systematic Biology. 67 (one): 127–144. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syx047. PMID 28472434.

- ^ a b c Salesa, G. J.; Peigné, Southward.; Antón, Yard. & Morales, J. (2021). "The taxonomy and phylogeny of Ailurus". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. xv–29. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ a b Salesa, M. J.; Mauricio, A.; Peigné, S. & Morales, J. (2006). "Evidence of a false pollex in a fossil carnivore clarifies the development of pandas". PNAS. 103 (ii): 379–382. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..379S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504899102. PMC1326154. PMID 16387860.

- ^ a b c d e Wallace, S. C. & Lyon, Fifty. (2021). "Systemic revision of the Ailurinae (Mammalia: Carnivora: Ailuridae): with a new species from North America". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Reddish Panda: Biology and Conservation of the Starting time Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 31–52. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ a b Wallace, S. C. & Wang, X. (2004). "Ii new carnivores from an unusual late Tertiary forest biota in eastern North America". Nature. 431 (7008): 556–559. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..556W. doi:10.1038/nature02819. PMID 15457257. S2CID 4432191.

- ^ Tedford, R. H. & Gustafson, E. P. (1977). "First North American tape of the extinct panda Parailurus". Nature. 265 (5595): 621–623. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..621T. doi:ten.1038/265621a0. S2CID 4214900.

- ^ Sotnikova, 1000. V. (2008). "A new species of bottom panda Parailurus (Mammalia, Carnivora) from the Pliocene of Transbaikalia (Russian federation) and some aspects of ailurine phylogeny". Paleontological Journal. 42 (ane): 90–99. doi:ten.1007/S11492-008-1015-10. S2CID 82000411.

- ^ Su, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, 50. & Chakraborty, R. (2001). "Genetic diversity and population history of the Carmine Panda (Ailurus fulgens) as inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence variations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. xviii (6): 1070–1076. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003878. PMID 11371595.

- ^ Hu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Ma, South.; Ma, T.; Shan, L.; Wang, X.; Nie, Y.; Ning, Z.; Yan, 50.; Xiu, Y. & Wei, F. (2017). "Comparative genomics reveals convergent evolution between the bamboo-eating giant and red pandas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (v): 1081–1086. doi:10.1073/pnas.1613870114. PMC5293045. PMID 28096377.

- ^ Shan, L.; Wu, Q.; Wange, L.; Zhang, L. & Wei, F. (2017). "Lineage-specific evolution of bitter taste receptor genes in the giant and reddish pandas implies dietary adaptation". Integrative Zoology. 13 (2): 152–159. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12291. PMC5873442. PMID 29168616.

- ^ a b c d e f grand Fisher, R. East. (2021). "Ruby Panda anatomy". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Ruby-red Panda: Biological science and Conservation of the Beginning Panda (2d ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 81–93. doi:x.1016/B978-0-12-823753-three.00030-ii. ISBN978-0-12-823753-three. S2CID 243824295.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j g Roberts, M. S. & Gittleman, J. L. (1984). "Ailurus fulgens" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 222 (222): one–8. doi:10.2307/3503840. JSTOR 3503840.

- ^ Makungu, M.; du Plessis, Due west. M.; Groenewald, H. B.; Barrows, M. & Koeppel, Thou. N. (2015). "Morphology of the pelvis and hind limb of the Reddish Panda (Ailurus fulgens) evidenced by gross osteology, radiography and computed tomography". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 44 (half-dozen): 410–421. doi:10.1111/ahe.12152. hdl:2263/50447. PMID 25308447. S2CID 13035672.

- ^ Antón, M.; Salesa, One thousand. J.; Pastor, J. F.; Peigné, S. & Morales, J. (2006). "Implications of the functional anatomy of the mitt and forearm of Ailurus fulgens (Carnivora, Ailuridae) for the evolution of the 'false-thumb' in pandas". Journal of Anatomy. 209 (6): 757–764. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00649.ten. PMC2049003. PMID 17118063.

- ^ Kong, F.; Zhao, J.; Han, S.; Zeng, B.; Yang, J.; Si, Ten.; Yang, B.; Yang, M.; Xu, H. & Li, Y. (2014). "Characterization of the gut microbiota in the red panda (Ailurus fulgens)". PLOS One. nine (2): e87885. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987885K. doi:ten.1371/journal.pone.0087885. PMC3912123. PMID 24498390.

- ^ a b Kandel, Chiliad.; Huettmann, F.; Suwal, Chiliad. K.; Regmi, Thou. R.; Nijman, Five.; Nekaris, Chiliad. A. I.; Lama, Due south. T.; Thapa, A.; Sharma, H. P. & Subedi, T. R. (2015). "Rapid multi-nation distribution cess of a charismatic conservation species using open access ensemble model GIS predictions: Cherry-red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the Hindu-Kush Himalaya region". Biological Conservation. 181: 150–161. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2014.10.007.

- ^ a b Mallick, J. K. (2010). "Status of Ruddy Panda Ailurus fulgens in Neora Valley National Park, Darjeeling Commune, West Bengal, India". Modest Carnivore Conservation. 43: 30–36.

- ^ a b c Dorji, S.; Rajaratnam, R. & Vernes, K. (2012). "The Vulnerable Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in Kingdom of bhutan: distribution, conservation, status and management recommendations". Oryx. 46 (4): 536–543. doi:10.1017/S0030605311000780. S2CID 84332758.

- ^ a b c Thapa, Grand.; Thapa, G. J.; Bista, D.; Jnawali, S. R.; Acharya, K. P.; Khanal, K.; Kandel, R. C.; Karki Thapa, M.; Shrestha, Due south.; Lama, S. T. & Sapkota, N. S. (2020). "Mural variables affecting the Himalayan Red Panda Ailurus fulgens occupancy in wet flavour along the mountains in Nepal". PLOS ONE. 15 (12): e0243450. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1543450T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243450. PMC7740865. PMID 33306732.

- ^ Dong, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, West. & Huang, Q. (2021). "Evaluating habitat suitability and potential dispersal corridors across the distribution landscape of the Chinese Carmine Panda (Ailurus styani) in Sichuan, Red china". Global Ecology and Conservation. 28: e01705. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01705.

- ^ a b c Lin, A. K.; Lwin, N.; Aung, Southward. S.; Oo, Due west. Northward.; Lum, L. Z. & Grindley, Thousand. (2021). "The conservation status of Cerise Panda in north-due east Myanmar". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Biological science and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 475–488. ISBN9780128237540.

- ^ Shrestha, South.; Lama, S.; Sherpa, A. P.; Ghale, D. & Lama, S. T. (2021). "The endangered Himalayan Red Panda: get-go photographic evidence from its westernmost distributon range". Periodical of Threatened Taxa. thirteen (five): 18156–18163. doi:10.11609/jott.6100.13.5.18156-18163.

- ^ a b c Bista, D.; Baxter, K. Southward.; Hudson, N. J.; Lama, Southward. T.; Weerman, J. & Murray, P. J. (2021). "Move and dispersal of a habitat specialist in human-dominated landscapes: a example report of the Red Panda". Movement Environmental. nine (1): 62. doi:10.1186/s40462-021-00297-z. PMC8670026. PMID 34906253.

- ^ a b Dalui, S.; Khatri, H.; Singh, S. K.; Basu, S.; Ghosh, A.; Mukherjee, T.; Sharma, L. K.; Singh, R.; Chandra, Thousand. & Thakur, M. (2020). "Fine-scale landscape genetics unveiling gimmicky asymmetric move of Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in Kangchenjunga landscape, India". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 15446. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1015446D. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-72427-3. PMC7508845. PMID 32963325.

- ^ a b c Panthi, South.; Aryal, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Lord, J. & Adhikari, B. (2012). "Summer diet and distribution of the Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens) in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Nepal". Zoological Studies. 51 (5): 701–709.

- ^ Khatiwara, S. & Srivastava, T. (2014). "Red Panda Ailurus fulgens and other small carnivores in Kyongnosla Tall Sanctuary, E Sikkim, India". Small Carnivore Conservation. 50: 35–38.

- ^ Bashir, T.; Bhattacharya, T.; Poudyal, One thousand. & Sathyakumar, South. (2019). "Beginning camera trap record of Red Panda Ailurus fulgens (Cuvier, 1825) (Mammalia: Carnivora: Ailuridae) from Khangchendzonga, Sikkim, Republic of india". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 11 (8): 14056–14061. doi:10.11609/jott.4626.xi.eight.14056-14061.

- ^ a b Chakraborty, R.; Nahmo, L. T.; Dutta, P. K.; Srivastava, T.; Mazumdar, K. & Dorji, D. (2015). "Status, affluence, and habitat associations of the Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in Pangchen Valley, Arunachal Pradesh, India". Mammalia. 79 (1): 25–32. doi:ten.1515/mammalia-2013-0105. S2CID 87668179.

- ^ Megha, M.; Christi, S.; Kapoor, M.; Gopal, R. & Solanki, R. (2021). "Photographic bear witness of Ruby Panda Ailurus fulgens Cuvier, 1825 from West Kameng and Shi-Yomi districts of Arunachal Pradesh, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. thirteen (9): 19254–19262. doi:10.11609/jott.6666.13.9.19254-19262.

- ^ Dong, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, W. & Huang, Q. (2021). "Evaluating habitat suitability and potential dispersal corridors across the distribution landscape of the Chinese crimson panda (Ailurus styani) in Sichuan, Communist china". Global Ecology and Conservation. 28: e01705. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01705.

- ^ a b c Wei, F.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z. & Hu, J. (1999). "Current distribution, status and conservation of wild Red Pandas Ailurus fulgens in China". Biological Conservation. 89 (three): 285–291. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00156-6.

- ^ Li, F.; Huang, X. Y.; Zhang, X. C.; Zhao, X. X.; Yang, J. H. & Chan, B. P. L. (2019). "Mammals of Tengchong Section of Gaoligongshan National Nature Reserve in Yunnan Province, Communist china". Periodical of Threatened Taxa. 11 (11): 14402–14414. doi:x.11609/jott.4439.11.xi.14402-14414.

- ^ a b c Wei, F.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z. & Hu, J. (2000). "Habitat employ and separation betwixt the Giant Panda and the Red Panda". Journal of Mammalogy. 81 (two): 448–455. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2000)081<0448:HUASBT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Dorji, S.; Vernes, Grand. & Rajaratnam, R. (2011). "Habitat correlates of the Cherry Panda in the temperate forests of Bhutan". PLOS ONE. vi (10): e26483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626483D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026483. PMC3198399. PMID 22039497.

- ^ Dendup, P.; Lham, C.; Wangchuk, J. & Tshering, K. (2018). "Winter habitat preferences of Endangered Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the Woods Enquiry Preserve of Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environmental Research, Bumthang, Bhutan". Journal of the Kingdom of bhutan Ecological Guild. 3: one–thirteen.

- ^ a b Dendup, P.; Humle, T.; Bista, D.; Penjor, U.; Lham, C. & Gyeltshen, J. (2020). "Habitat requirements of the Himalayan Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) and threat analysis in Jigme Dorji National Park, Bhutan". Ecology and Evolution. 10 (17): 9444–9453. doi:x.1002/ece3.6632. PMC7487235. PMID 32953073.

- ^ a b Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Li, K. & Hu, J. (2006). "Winter microhabitat separation between Giant and Red Pandas in Bashania faberi Bamboo forest in Fengtongzhai Nature Reserve". The Journal of Wildlife Direction. seventy (1): 231–235. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[231:WMSBGA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Dendup, P.; Lham, C.; Wangchuk, J. & Tshering, One thousand. (2018). "Winter habitat preferences of Endangered Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the Forest Enquiry Preserve of Ugyen Wangchuck Plant for Conservation and Ecology Research, Bumthang, Bhutan". Journal of the Bhutan Ecological Order. 3: 1–13.

- ^ Zhou, X.; Jiao, H.; Dou, Y.; Aryal, A.; Hu, J.; Hu, J. & Meng, 10. (2013). "The winter habitat option of Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the Meigu Dafengding National Nature Reserve, Communist china". Current Science. 105 (10): 1425–1429.

- ^ Liu, X.; Teng, L.; Ding, Y. & Liu, Z. (2021). "Habitat selection by Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens) in Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, China" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of Zoology. doi:10.17582/periodical.pjz/20190726090725. S2CID 238963119.

- ^ a b Gebauer, A. (2021). "The early days: maternal behaviour and infant development". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Scarlet Panda: Biology and Conservation of the Beginning Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 149–179. ISBN978-0-12-823753-three.

- ^ Karki, S.; Maraseni, T.; Mackey, B.; Bista, D.; Lama, Southward. T.; Gautam, A. P.; Sherpa, A. P.; Koju, A. P.; Koju, U.; Shrestha, A. & Cadman, T. (2021). "Reaching over the gap: A review of trends in and status of red panda enquiry over 193 years (1827–2020)". Science of the Full Surround. 781: 146659. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.781n6659K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146659. PMID 33794452. S2CID 232763016.

- ^ a b Reid, D. G.; Jinchu, H. & Yan, H. (1991). "Ecology of the Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in the Wolong Reserve, China". Periodical of Zoology. 225 (3): 347–364. doi:x.1111/j.1469-7998.1991.tb03821.x.

- ^ a b Bista, D.; Baxter, M. S.; Hudson, N. J.; Lama, South. T. & Murray, P. J. (2021). "Effect of disturbances and habitat fragmentation on an arboreal habitat specialist mammal using GPS telemetry: a case of the red panda". Mural Ecology: 1–xv. doi:10.1007/s10980-021-01357-due west. PMC8542365. PMID 34720409.

- ^ Nijboer, J. & Dierenfeld, E. S. (2021). "Red panda diet: how to feed a vegetarian carnivore". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 225–238. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ Wei, F.; Thapa, A.; Hu, Y. & Zhang, Z. (2021). "Scarlet Panda ecology". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biological science and Conservation of the Starting time Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 329–351. ISBN978-0-12-823753-iii.

- ^ WFO (2022). "Arundinaria maling Risk". World Flora Online. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ WFO (2022). "Arundinaria aristata Gamble". World Flora Online. Retrieved eight Feb 2022.

- ^ Pradhan, S.; Saha, G. Grand. & Khan, J. A. (2001). "Ecology of the Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in the Singhalila National Park, Darjeeling, India". Biological Conservation. 98: xi–xviii. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00079-3.

- ^ Roka, B.; Jha, A. K. & Chhetri, D. R. (2021). "A study on plant preferences of Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the wild habitat: foundation for the conservation of the species". Acta Biologica Sibirica. seven: 425–439. doi:x.3897/abs.7.e71816. S2CID 244942192.

- ^ Sharma, H. R.; Swenson, J. E. & Belant, J. (2014). "Seasonal food habits of the Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in Rara National Park, Nepal". Hystrix. 25 (1): 47–50. doi:10.4404/hystrix-25.1-9033.

- ^ Wei, F.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, A. & Hu, J. (1999). "Apply of the nutrients in bamboo by the Cerise Panda Ailurus fulgens". Periodical of Zoology. 248 (4): 535–541. doi:x.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01053.10.

- ^ Qi, D.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Due west.; Lei, G.; Yuan, Due south.; Qi, D. & Zhang, Z. (2016). "Vocal repertoire of adult convict red pandas (Ailurus fulgens)". Animal Biology. 66 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1163/15707563-00002493.

- ^ a b Curry, E. (2021). "Reproductive biology of the Ruddy Panda". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 119–138. ISBN978-0-12-823753-three.

- ^ Roberts, M. S. & Kessler, D. South. (1979). "Reproduction in Red pandas, Ailurus fulgens (Carnivora : Ailuropodidae)". Periodical of Zoology. 188 (2): 235–249. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1979.tb03402.x.

- ^ Lama, S. T.; Lama, R. P.; Regmi, G. R. & Ghimire, T. R. (2015). "Prevalence of abdominal parasitic infections in complimentary-ranging Red Panda Ailurus fulgens Cuvier, 1825 (Mammalia: Carnivora: Ailuridae) in Nepal". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 7 (eight): 7460–7464. doi:10.11609/JoTT.o4208.7460-4.

- ^ Bista, D.; Shrestha, South.; Kunwar, A. J.; Acharya, S.; Jnawali, S. R. & Acharya, K. P. (2017). "Status of gastrointestinal parasites in Red Panda of Nepal". PeerJ. 5: e3767. doi:ten.7717/peerj.3767. PMC5591639. PMID 28894643.

- ^ Sharma, H. P. & Achhami, B. (2021). "Gastro‐intestinal parasites of sympatric Red Panda and livestock in protected areas of Nepal". Veterinarian Medicine and Science. doi:ten.1002/vms3.651. PMID 34599791. S2CID 238250774.

- ^ Kearns, K. South.; Pollock, C. 1000. & Ramsay, E. C. (1999). "Dermatophytosis in Red Pandas (Ailurus fulgens fulgens): a review of 14 cases". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. xxx (4): 561–563. JSTOR 20095922. PMID 10749446.

- ^ Huckins, Yard. L.; Eshar, D.; Schwartz, D.; Morton, Chiliad.; Herrin, B. H.; Cerezo, A.; Yabsley, Yard. J. & Schneider, S. M. (2019). "Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a zoo-housed Red Panda in Kansas". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 31 (v): 752–755. doi:10.1177/1040638719865926. PMC6727118. PMID 31342874.

- ^ Alex, C. East.; Kubiski, Southward. 5.; Li, Fifty.; Sadeghi, Thou.; Wack, R. F.; McCarthy, Yard. A.; Pesavento, J. B.; Delwart, Due east. & Pesavento, P. A. (2018). "Amdoparvovirus infection in Red Pandas (Ailurus fulgens)". Veterinarian Pathology. 55 (4): 552–561. doi:10.1177/0300985818758470. PMID 29433401.

- ^ Yang, Y.; Dong, H.; Su, R.; Li, T.; Jiang, N.; Su, C. & Zhang, L. (2019). "Testify of Red Panda equally an intermediate host of Toxoplasma gondii and Sarcocystis species". International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wild fauna. 8: 188–191. doi:x.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.02.006. PMC6403407. PMID 30891398.

- ^ Liu, Due south.; Li, Y.; Yue, C.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Yan, X.; Yang, 1000.; Chen, 10.; Zhuo, K.; Cai, T.; Liu, J.; Peng, X. & Huo, R. (2020). "Isolation and label of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) from Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens)". BMC Veterinary Research. 16 (one): 404. doi:10.1186/s12917-020-02624-9. PMC7590469. PMID 33109179.

- ^ a b Glatson, A. R. (1994). "The Red Panda or Bottom Panda (Ailurus fulgens)" (PDF). Status Survey and Conservation Action Programme for Procyonids and Ailurids. The Red Panda, Olingos, Coatis, Raccoons, and their Relatives. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Mustelid, Viverrid, and Procyonid Specialist Grouping. pp. 8, viii–11, xix–21. ISBN2-8317-0046-9.

- ^ Yonzon, P. B. & Hunter, M. L. Jr. (1991). "Conservation of the Red Panda Ailurus fulgens". Biological Conservation. 57 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90046-C.

- ^ Acharya, K. P.; Shrestha, S.; Paudel, P. Chiliad.; Sherpa, A. P.; Jnawali, Southward. R.; Acharya, Southward. & Bista, D. (2018). "Pervasive human being disturbance on habitats of endangered Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in the central Himalaya". Global Environmental and Conservation. xv: e00420. doi:x.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00420. S2CID 92988737.

- ^ Ghimire, G.; Pearch, G.; Baral, B.; Thapa, B. & Baral, R. (2019). "The get-go photographic tape of the Red Panda Ailurus fulgens (Cuvier, 1825) from Lamjung District exterior Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal". Periodical of Threatened Taxa. 11 (12): 14576–14581. doi:10.11609/jott.4828.11.12.14576-14581.

- ^ Bista, D.; Baxter, G. S. & Murray, P. J. (2020). "What is driving the increased demand for reddish panda pelts?". Human being Dimensions of Wild animals. 25 (4): 324–338. doi:x.1080/10871209.2020.1728788. S2CID 213958948.

- ^ Xu, 50. & Guan, J. (2018). Red Panda marketplace research findings in China (PDF). Cambridge: Traffic.

- ^ Datta, A.; Naniwadekar, R. & Anand, Grand. O. (2008). "Occurrence and conservation status of small carnivores in 2 protected areas in Arunachal Pradesh, north-e India". Minor Carnivore Conservation. 39: 1–10.

- ^ Lwin, Y. H.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Maung, G. West.; Swa, Thousand. & Quan, R. C. (2021). "Diversity, distribution and conservation of large mammals in northern Myanmar". Global Ecology and Conservation. 29: e01736. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01736.

- ^ Li, X.; Bleisch, Westward. Five.; Liu, X. & Jiang, X. (2021). "Camera-trap surveys reveal high diversity of mammals and pheasants in Medog, Tibet". Oryx. 55 (ii): 177–180. doi:x.1017/S0030605319001467.

- ^ a b Wei, F.; Zhang, Z.; Thapa, A.; Zhijin, Fifty. & Hu, Y. (2021). "Conservation initiatives in China". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Blood-red Panda: Biological science and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Printing. pp. 509–520. doi:x.1016/B978-0-12-823753-3.00021-ane. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3. S2CID 243813871.

- ^ Thapa, A.; Hu, Y. & Wei, F. (2018). "The endangered Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens): Ecology and conservation approaches across the entire range". Biological Conservation. 220: 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.02.014.

- ^ Bista, D. (2018). "Communities in frontline in Scarlet Panda conservation, eastern Nepal" (PDF). The Himalayan Naturalist. one (1): xi–12.

- ^ Sherpa, A. P.; Lama, South. T.; Shrestah, Southward.; Williams, B. & Bista, D. (2021). "Cerise Pandas in Nepal: community-based arroyo to mural-level conservation". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Scarlet Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 495–508. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-823753-3.00019-iii. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3. S2CID 243829246.

- ^ Millar, J. & Tenzing, K. (2021). "Transforming degraded rangelands and pastoralists' livelihoods in eastern Bhutan". Mount Research and Development. 41 (4): D1–D7. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-21-00025.1.

- ^ Jones, Thousand. L. (2021). "A brief history of the Cerise Panda in captivity". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Reddish Panda: Biology and Conservation of the Beginning Panda (Second ed.). London: Bookish Press. pp. 181–199. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-823753-3.00026-0. ISBN978-0-12-823753-3. S2CID 243805749.

- ^ Lewis, K. (2011). "Nascency and mother rearing of Nepalese red pandas Ailurus fulgens fulgens at the Taronga Conservation Society Commonwealth of australia". International Zoo Yearbook. 45 (1): 250–258. doi:x.1111/j.1748-1090.2011.00135.x.

- ^ Kappelhof, J. & Weerman, J. (2020). "The development of the Red panda Ailurus fulgens EEP: from a failing captive population to a stable population that provides effective back up to in situ conservation". International Zoo Yearbook. 54 (1): 102–112. doi:10.1111/izy.12278.

- ^ Tanaka, A. & Ogura, T. (2018). "Current husbandry situation of Cerise Pandas in Japan". Zoo Biological science. 37 (two): 107–114. doi:ten.1002/zoo.21407. PMID 29512188.

- ^ Kumar, A.; Rai, U.; Roka, B.; Jha, A. K. & Reddy, P. A. (2016). "Genetic assessment of captive red panda (Ailurus fulgens) population". SpringerPlus. 5 (1): 1750. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3437-one. PMC5055525. PMID 27795893.

- ^ a b Glatston, A. R. & Gebauer, A. (2021). "People and Red Pandas: the Red Panda's function in economy and culture". In Glatston, A. R. (ed.). Ruddy Panda: Biological science and Conservation of the First Panda (Second ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 1–xiv. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-823753-iii.00002-8. ISBN9780128237540. S2CID 243805192.

- ^ Lowther, D. A. (2021). "The offset painting of the Carmine Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in Europe? Natural history and artistic patronage in early nineteenth-century India". Archives of Natural History. 48 (2): 368–376. doi:10.3366/anh.2021.0728. S2CID 244938631.

External links

- Red Panda Network – a non-profit organisation for red panda conservation

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_panda

0 Response to "Is Red Pandas Part of the Panda Family"

Post a Comment